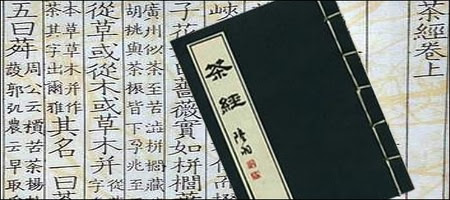

차의 역사를 이야기할 때, 신화와 전설을 넘어 비로소 체계적인 이론과 실천의 세계로 이끌어낸 인물이 있습니다. 바로 중국 당나라 시대를 살았던 육우(陸羽, 733?~804?)입니다. 그는 차에 대한 깊은 애정과 해박한 지식으로 인류 최초의 차 전문 서적인 『다경(茶經)』을 저술하여, 흩어져 있던 차 관련 지식과 경험을 하나로 모아 집대성했습니다. 더 나아가 그는 차 마시는 행위를 단순한 일상의 습관이 아닌 하나의 예술이자 철학의 영역으로 끌어올렸습니다. 이러한 공로로 육우는 후대에 '차의 성인', 즉 '다성(茶聖)'이라 불리게 되었습니다.

육우가 살았던 당나라는 차 문화가 크게 융성했던 시대였습니다. 궁궐에서부터 민간에 이르기까지 차를 마시는 것이 일반화되었지만, 정작 차에 대한 체계적인 지식은 부족했습니다. 각 지역마다, 각 가문마다 전해 내려오는 방식이 제각각이었고, 좋은 차를 구별하거나 제대로 우려내는 방법도 경험에만 의존하고 있었습니다. 이런 상황에서 육우는 평생에 걸쳐 중국 각지를 돌아다니며 차밭을 살펴보고, 차 만드는 장인들을 만나며, 다양한 차를 직접 맛보고 연구했습니다. 그리고 이 모든 경험과 지식을 『다경』이라는 한 권의 책으로 완성해냈습니다.

『다경』은 오늘날의 기준으로 보아도 놀라울 만큼 상세하고 방대한 내용을 담고 있습니다. 총 3권 10장으로 구성된 이 책은 차에 대한 거의 모든 것을 다루고 있는데, 그 구성을 살펴보면 육우의 치밀함과 체계적 사고를 엿볼 수 있습니다.

첫 번째 장 '일지원(一之源)'에서는 차의 근본을 탐구합니다. 육우는 신농씨가 우연히 차를 발견했다는 전설부터 시작하여, 차나무의 생물학적 특성을 상세히 기록했습니다. 그는 차나무가 남쪽의 따뜻한 산간 지역에서 자라며, 잎의 크기와 모양, 생육 환경에 따라 품질이 달라진다는 점을 관찰했습니다. 또한 차를 가리키는 다양한 명칭들 - 차(茶), 가(檟), 설(設), 명(茗), 천(荈) 등의 어원과 의미를 설명하면서, 차가 단순한 식물이 아니라 문화적 의미를 지닌 존재임을 강조했습니다.

두 번째 장 '이지구(二之具)'는 차를 채취하는 도구들을 다룹니다. 육우는 찻잎을 따는 시기와 방법이 차의 품질을 좌우한다고 보았습니다. 이른 봄 새순이 돋아날 때, 이슬이 마르고 햇살이 부드러운 오전 시간에 따야 하며, 이때 사용하는 칼과 바구니, 도구들의 재질과 크기까지 구체적으로 제시했습니다. 특히 찻잎을 상하지 않게 보관하는 방법과 운반 과정에서의 주의사항도 자세히 기록했는데, 이는 현대의 차 생산에서도 여전히 중요한 원칙으로 여겨집니다.

세 번째 장 '삼지조(三之造)'는 제차법, 즉 차를 만드는 과정을 설명합니다. 당시 주류였던 떡차 형태의 '단차(團茶)'와 '병차(餠茶)' 제조법을 중심으로, 찻잎을 쪄서 으깨고 압축하여 성형하는 복잡한 과정을 단계별로 기록했습니다. 육우는 각 단계에서 온도와 시간, 압력을 조절하는 것이 얼마나 중요한지 강조했으며, 숙련된 장인의 손길이 어떻게 차의 맛과 향을 결정하는지 생생하게 묘사했습니다. 또한 완성된 차를 보관하는 방법과 좋은 차를 구별하는 법도 함께 제시했습니다.

네 번째 장 '사지기(四之器)'는 차를 우려내는 데 필요한 도구들을 체계적으로 정리했습니다. 육우는 총 24가지의 도구를 소개했는데, 각각의 이름과 용도, 재질, 크기까지 상세히 기록했습니다. 예를 들어 물을 끓이는 부(釜)는 철로 만들어야 하고 적당한 두께를 가져야 한다고 했으며, 차를 젓는 칙(則)은 대나무나 철로 만들되 손잡이 길이까지 구체적으로 제시했습니다. 찻잔인 완(椀)의 경우 청자나 백자를 권했는데, 이는 차의 색깔을 제대로 감상할 수 있기 때문이라고 설명했습니다. 이처럼 각 도구가 단순한 기물이 아니라 차의 품질과 직결되는 중요한 요소임을 강조했습니다.

다섯 번째 장 '오지자(五之煮)'는 차를 끓이는 핵심 기술을 다룹니다. 육우는 먼저 물의 중요성을 강조하며, 산속 샘물이 가장 좋고 강물이 그 다음, 우물물은 가장 낮은 등급이라고 평가했습니다. 물을 끓일 때는 첫 번째 끓음, 두 번째 끓음, 세 번째 끓음을 구분해야 하며, 두 번째 끓음에서 소금을 넣고 세 번째 끓음에서 찻가루를 넣어야 한다고 했습니다. 이때 물의 표면에 생기는 거품의 상태를 보고 불의 세기를 조절하는 방법, 찻가루를 넣는 순간의 타이밍과 젓는 방법까지 마치 과학 실험을 하듯 정밀하게 기록했습니다. 또한 날씨와 계절에 따라 끓이는 시간과 방법을 조절해야 한다는 점도 언급했습니다.

여섯 번째 장 '육지음(六之飲)'에서는 차를 마시는 예절과 문화를 정립했습니다. 육우는 차를 혼자 마실 때와 여러 명이 함께 마실 때의 차이점을 설명하며, 최대 열 명까지 함께 마시는 것이 적당하다고 했습니다. 차를 마시는 순서, 찻잔을 잡는 방법, 차를 음미하는 자세 등을 제시하면서, 차를 마시는 행위 자체가 하나의 예술이자 수양의 과정이 되도록 했습니다. 또한 차와 어울리는 음식이나 분위기, 계절과 시간대에 따른 차 마시기의 차이점도 언급했는데, 이는 차 문화가 일상생활 전반에 스며들 수 있는 철학적 토대를 마련한 것입니다.

일곱 번째 장 '칠지사(七之事)'는 차의 역사를 정리한 부분입니다. 육우는 고대 문헌에 나타난 차 관련 기록들을 수집하여 시대순으로 정리했습니다. 주나라 때부터 당나라에 이르기까지 차가 어떻게 발전해왔는지, 어떤 인물들이 차와 관련된 일화를 남겼는지 상세히 기록했습니다. 특히 차를 사랑했던 역사 인물들의 이야기를 통해 차가 단순한 음료가 아니라 문인들의 정신세계와 깊이 연결되어 있음을 보여주었습니다. 이는 차에 역사적 정당성과 문화적 권위를 부여하는 중요한 작업이었습니다.

여덟 번째 장 '팔지출(八之出)'에서는 중국 각지의 차 산지를 소개하고 품질을 평가했습니다. 육우는 직접 발로 뛰어 조사한 결과를 바탕으로 각 지역 차의 특징을 비교 분석했습니다. 예를 들어 저장성의 차는 맛이 달고 부드럽고, 후난성의 차는 진하고 쓴맛이 강하다는 식으로 구체적인 특성을 기록했습니다. 또한 같은 지역 내에서도 산의 방향, 고도, 토양의 성질에 따라 차의 품질이 달라진다는 점을 지적하며, 최고급 차가 나는 곳부터 차례로 순위를 매기기도 했습니다. 이는 현대의 테루아(terroir) 개념과도 일맥상통하는 선진적인 관점이었습니다.

아홉 번째 장 '구지략(九之略)'은 특별한 장입니다. 육우는 『다경』에서 제시한 복잡한 과정들이 모든 상황에서 반드시 지켜져야 하는 것은 아니라고 인정했습니다. 예를 들어 산속이나 들판에서 차를 마실 때, 또는 급하게 차를 마셔야 할 때는 일부 과정을 생략할 수 있다고 했습니다. 이는 『다경』이 융통성 없는 교조가 아니라 실용적인 지침서임을 보여주는 동시에, 차 문화가 형식에 얽매이지 않고 본질을 추구해야 한다는 육우의 철학을 담고 있습니다.

마지막 열 번째 장 '십지도(十之圖)'는 『다경』의 내용을 그림으로 정리한 부분입니다. 비록 원본 그림은 전해지지 않지만, 육우는 복잡한 내용을 시각적으로 이해할 수 있도록 도표와 그림을 활용했습니다. 차나무의 모습부터 각종 도구들, 제차 과정, 우리는 방법까지 그림으로 표현하여 글로는 설명하기 어려운 부분들을 보완했습니다. 이는 현대의 매뉴얼이나 가이드북에서 사용하는 방식과 매우 유사한 접근법으로, 육우의 실용적 사고를 엿볼 수 있는 부분입니다.

『다경』이 지닌 가장 큰 의미는 바로 차에 대한 모든 것을 체계적으로 정리했다는 점입니다. 이전까지 파편적으로 전해지던 차 관련 지식과 경험을 하나의 완성된 틀 안에 담아냄으로써, 차는 비로소 누구든 배우고 따라 할 수 있는 구체적인 실천 영역이 되었습니다. 이는 차 문화가 특정 계층의 전유물에서 벗어나 더 넓은 범위로 확산되고 발전하는 데 결정적인 기반이 되었습니다. 마치 요리에 레시피가 있듯이, 차에도 명확한 가이드라인이 생긴 셈입니다.

더욱 중요한 것은 『다경』이 차 마시는 행위에 정신적인 가치와 미학을 부여했다는 점입니다. 육우는 차를 고르는 것부터 물을 준비하고 끓여 마시는 전 과정에 정성을 다하고 마음을 집중해야 함을 강조했습니다. 그는 차 마시는 시간을 단순한 갈증 해소가 아닌 성찰과 사색, 교류의 시간으로 승화시켰습니다. 이러한 사상은 이후 동아시아 각국에서 다도(茶道)라는 정신적인 수행으로 발전하는 데 중요한 철학적 토대가 되었습니다.

실제로 차를 마셔보신 분들은 아시겠지만, 좋은 차 한 잔을 우려내는 과정에는 참으로 많은 변수가 있습니다. 찻잎의 상태, 물의 온도, 우리는 시간, 심지어 그날의 기분과 날씨까지도 차 맛에 영향을 미칩니다. 육우는 이 모든 요소들을 세심하게 관찰하고 기록했으며, 무엇보다 차를 대하는 마음가짐의 중요성을 역설했습니다. 그에게 차는 단순한 음료가 아니라 자연과 인간이 만나는 지점이었고, 일상의 분주함 속에서 잠시 멈춰 자신을 돌아보는 시간이었습니다.

육우의 『다경』은 중국은 물론이고 한국, 일본 등 주변국으로 전파되어 각국의 차 문화 발달에도 지대한 영향을 미쳤습니다. 한국의 전통 차 문화나 일본의 다도에서 찾아볼 수 있는 정신적 깊이와 예술적 완성도는 모두 『다경』의 철학에서 출발했다고 해도 과언이 아닙니다. 『다경』 덕분에 차는 인류 문명 속에서 더욱 확고한 자리를 잡았고, 오늘날까지도 전 세계인에게 사랑받는 음료이자 깊은 문화적 의미를 지닌 존재로 남아있습니다.

천 년이 넘는 세월이 흘렀지만 『다경』은 여전히 차의 '교과서'로서, 시대를 초월하여 차를 사랑하는 모든 이들에게 변함없는 가르침을 주고 있습니다. 현대의 차 애호가들도 여전히 『다경』에서 제시한 원칙들을 따르고 있으며, 육우가 강조한 '차를 통한 정신적 수양'이라는 가치는 바쁜 현대인들에게 더욱 소중한 의미로 다가오고 있습니다.

🍵 흑차 구입은 트릿티 App으로(무료 회원 가입하고 건강 챙기고 돈도 벌고) :

최고의 프리미엄 흑차와 함께 누리는 건강하고 풍유로운 삶!! - https://mall.gm2xtea.com/#/pages/loginRegist/regist?shareCode=zeongmae1824

TreatTea

mall.gm2xtea.com

https://youtu.be/Q9i06rq4zvs?si=d5BwFD8F5j98vwK-

Systematization of Tea Culture in Lu Yu’s The Classic of Tea

When we speak of the history of tea, there is one figure who led tea from the realm of myths and legends into a systematic world of theory and practice. That person is Lu Yu (陸羽, 733?–804?) of the Tang Dynasty in China. With deep affection for and profound knowledge of tea, Lu Yu authored The Classic of Tea (Cha Jing, 茶經), the world’s first monograph on tea. He compiled scattered knowledge and experiences about tea into one coherent work. Furthermore, he elevated tea drinking from a daily habit to a realm of art and philosophy. For these contributions, he has been honored by later generations as the “Sage of Tea” (Cha Sheng, 茶聖).

The Tang Dynasty, during which Lu Yu lived, was a golden era for tea culture. From the imperial court to common households, tea drinking was common, yet systematic knowledge about tea was lacking. Tea practices varied by region and family traditions, and methods for identifying quality tea or brewing it properly relied solely on experience. In response to this, Lu Yu spent his life traveling across China, visiting tea plantations, meeting tea artisans, and personally tasting and studying various teas. He distilled all these observations and knowledge into a single book: The Classic of Tea.

Even by today’s standards, The Classic of Tea is astonishingly detailed and comprehensive. Comprising 3 volumes and 10 chapters, the book covers virtually every aspect of tea. Its structure reveals Lu Yu’s meticulous and systematic thinking.

The first chapter, Origin (一之源), explores the roots of tea. Beginning with the legend of Shennong discovering tea, Lu Yu recorded the botanical characteristics of the tea plant. He noted that tea grows in warm southern mountainous regions and that its quality varies based on leaf size, shape, and environmental conditions. He also explained the various names for tea—cha (茶), jia (檟), she (設), ming (茗), chuan (荈)—emphasizing its cultural significance beyond being a mere plant.

The second chapter, Tools (二之具), covers the tools for harvesting tea. Lu Yu believed that the time and method of picking tea leaves determined their quality. He recommended harvesting in early spring, after the dew has dried, and during mild morning sunlight. He specified the materials, size, and types of knives and baskets to be used, and detailed how to preserve and transport leaves carefully. These insights remain relevant in modern tea production.

The third chapter, Processing (三之造), outlines the tea-making process. Focused on the common forms of compressed tea at the time—tuancha (round tea cakes) and bingcha (flat tea cakes)—Lu Yu recorded the steaming, pounding, and shaping steps in detail. He stressed the importance of controlling temperature, timing, and pressure, and described how skilled craftsmanship influences flavor and aroma. He also discussed storage methods and how to identify high-quality tea.

The fourth chapter, Utensils (四之器), systematically lists the tools for brewing tea. Lu Yu introduced 24 utensils, describing their names, uses, materials, and sizes. For instance, kettles (fu, 釜) should be made of iron with appropriate thickness, while stirring tools (ze, 則) should be bamboo or iron with specific handle lengths. Teacups (wan, 椀) were best made of celadon or white porcelain to appreciate the tea’s color. Lu Yu emphasized that these tools were crucial to the quality of tea, not merely auxiliary items.

The fifth chapter, Boiling (五之煮), is about the art of boiling tea. Lu Yu placed high importance on water quality—spring water was best, followed by river water, with well water being the least desirable. He categorized boiling into three stages: during the second boil, salt was to be added, and during the third, powdered tea. He gave precise instructions on adjusting heat based on the bubbles and timing for adding ingredients, like a scientific experiment. He even considered seasonal and weather-based variations.

The sixth chapter, Drinking (六之飲), defines tea etiquette and culture. Lu Yu described how solo and group tea drinking differed, suggesting a maximum of ten people for group settings. He provided guidance on the order of serving, how to hold the cup, and how to savor tea. He also discussed the appropriate food pairings, atmospheres, and seasonal differences, laying a philosophical foundation for tea to permeate daily life.

The seventh chapter, Historical Accounts (七之事), compiles tea’s historical records. Lu Yu collected and arranged documents about tea from ancient texts, tracing its development from the Zhou Dynasty to the Tang. He highlighted stories of notable tea lovers, showing how tea was deeply connected to intellectual and spiritual life. This work granted tea both historical legitimacy and cultural prestige.

The eighth chapter, Production Regions (八之出), introduces China’s tea-producing regions and evaluates their quality. Based on firsthand research, Lu Yu compared the taste profiles of different areas—Zhejiang teas were sweet and smooth, while Hunan teas were strong and bitter. He noted how direction, altitude, and soil type affected quality, ranking regions accordingly. This reflects an early understanding of what we now call terroir.

The ninth chapter, Simplification (九之略), is a unique one. Lu Yu admitted that not all procedures needed to be followed rigidly in all circumstances. In the mountains or when tea had to be made quickly, steps could be omitted. This practical stance showed that The Classic of Tea was not dogmatic but adaptable, and it reflects his belief that tea culture should pursue essence over form.

The tenth and final chapter, Illustrations (十之圖), summarized the content with visual aids. Though the original drawings are lost, Lu Yu used diagrams to explain the tea plant, tools, processing, and brewing methods. These visuals, similar to today’s manuals or guidebooks, show Lu Yu’s practical thinking.

The greatest significance of The Classic of Tea lies in its systematic compilation of all things tea-related. By organizing scattered knowledge into a comprehensive structure, tea became an accessible and teachable practice. Like a recipe in cooking, tea finally had its guidebook.

Even more importantly, Lu Yu imbued tea drinking with spiritual and aesthetic value. He emphasized mindfulness and intention at every stage—from selecting leaves to boiling water and sipping the brew. For him, tea was not just a beverage but a meeting point between nature and humanity, and a pause for reflection amid daily busyness.

The Classic of Tea spread to Korea, Japan, and other neighboring countries, greatly influencing their tea cultures. The spiritual depth and artistic refinement seen in Korean and Japanese tea ceremonies owe much to Lu Yu’s philosophy. Thanks to The Classic of Tea, tea secured its cultural place in human civilization and continues to be cherished worldwide.

Even after more than a thousand years, The Classic of Tea remains a timeless textbook for tea lovers. Its principles are still followed today, and its message of spiritual cultivation through tea resonates even more deeply with modern people.